Canadian legal firearm definitions are spread-out across a few legal resources and can be difficult to navigate. Below are excerpts from some of the most commonly used resources. (This page is a consolidation of excerpts from published information and is intended for general information purposes only, please refer to the original cited sources for the most current and accurate definitions).

CRIMINAL CODE OF CANADA

The Criminal Code of Canada has a few relevant sections that cover most questions related to firearm definitions. Section 2 of the Criminal Code of Canada contains a the legal definition of firearm. Part 3, Section 84 of the criminal code is the section of the Criminal Code that contains most of the definitions related to firearms.

Section 2 Firearm Definition

Firearm means a barrelled weapon from which any shot, bullet or other projectile can be discharged and that is capable of causing serious bodily injury or death to a person, and includes any frame or receiver of such a barrelled weapon and anything that can be adapted for use as a firearm;

Section 84(1) Definitions

ammunition means a cartridge containing a projectile designed to be discharged from a firearm and, without restricting the generality of the foregoing, includes a caseless cartridge and a shot shell;

antique firearm means

(a) any firearm manufactured before 1898 that was not designed to discharge rim-fire or centre-fire ammunition and that has not been redesigned to discharge such ammunition, or

(b) any firearm that is prescribed to be an antique firearm; (see Antique Regulations)

automatic firearm means a firearm that is capable of, or assembled or designed and manufactured with the capability of, discharging projectiles in rapid succession during one pressure of the trigger;

cartridge magazine means a device or container from which ammunition may be fed into the firing chamber of a firearm; (See Magazine Regulations)

cross-bow means a device with a bow and a bowstring mounted on a stock that is designed to propel an arrow, a bolt, a quarrel or any similar projectile on a trajectory guided by a barrel or groove and that is capable of causing serious bodily injury or death to a person;

handgun means a firearm that is designed, altered or intended to be aimed and fired by the action of one hand, whether or not it has been redesigned or subsequently altered to be aimed and fired by the action of both hands;

non-restricted firearm means

(a) a firearm that is neither a prohibited firearm nor a restricted firearm, or

(b) a firearm that is prescribed to be a non-restricted firearm;

prescribed means prescribed by the regulations;

prohibited ammunition means ammunition, or a projectile of any kind, that is prescribed to be prohibited ammunition;

prohibited device means

(a) any component or part of a weapon, or any accessory for use with a weapon, that is prescribed to be a prohibited device,

(b) a handgun barrel that is equal to or less than 105mm in length, but does not include any such handgun barrel that is prescribed, where the handgun barrel is for use in international sporting competitions governed by the rules of the International Shooting Union,

(c) a device or contrivance designed or intended to muffle or stop the sound or report of a firearm,

(d) a cartridge magazine that is prescribed to be a prohibited device, or

(e) a replica firearm;

prohibited firearm means

(a) a handgun that (i) has a barrel equal to or less than 105 mm in length, or

(ii) is designed or adapted to discharge a 25 or 32 calibre cartridge, but does not include any such handgun that is prescribed, where the handgun is for use in international sporting competitions governed by the rules of the International Shooting Union,

(b) a firearm that is adapted from a rifle or shotgun, whether by sawing, cutting or any other alteration, and that, as so adapted,

(i) is less than 660 mm in length, or

(ii) is 660 mm or greater in length and has a barrel less than 457 mm in length,

(c) an automatic firearm, whether or not it has been altered to discharge only one projectile with one pressure of the trigger, or

(d) any firearm that is prescribed to be a prohibited firearm;

replica firearm means any device that is designed or intended to exactly resemble, or to resemble with near precision, a firearm, and that itself is not a firearm, but does not include any such device that is designed or intended to exactly resemble, or to resemble with near precision, an antique firearm;

restricted firearm means

(a) a handgun that is not a prohibited firearm,

(b) a firearm that (i) is not a prohibited firearm,

(ii) has a barrel less than 470 mm in length, and

(iii) is capable of discharging centre-fire ammunition in a semi-automatic manner,

(c) a firearm that is designed or adapted to be fired when reduced to a length of less than 660 mm by folding, telescoping or otherwise, or

(d) a firearm of any other kind that is prescribed to be a restricted firearm;

84(2) Barrel length Definition

(2) For the purposes of this Part, the length of a barrel of a firearm is

(a) in the case of a revolver, the distance from the muzzle of the barrel to the breach end immediately in front of the cylinder, and

(b) in any other case, the distance from the muzzle of the barrel to and including the chamber, but does not include the length of any component, part or accessory including any component, part or accessory designed or intended to suppress the muzzle flash or reduce recoil.

84(3) Certain weapons deemed not to be firearms

(3) For the purposes of sections 91 to 95, 99 to 101, 103 to 107 and 117.03 of this Act and the provisions of the Firearms Act, the following weapons are deemed not to be firearms:

(a) any antique firearm;

(b) any device that is

(i) designed exclusively for signalling, for notifying of distress, for firing blank cartridges or for firing stud cartridges, explosive-driven rivets or other industrial projectiles, and

(ii) intended by the person in possession of it to be used exclusively for the purpose for which it is designed;

(c) any shooting device that is

(i) designed exclusively for the slaughtering of domestic animals, the tranquillizing of animals or the discharging of projectiles with lines attached to them, and

(ii) intended by the person in possession of it to be used exclusively for the purpose for which it is designed; and

(d) any other barrelled weapon, where it is proved that the weapon is not designed or adapted to discharge

(i) a shot, bullet or other projectile at a muzzle velocity exceeding 152.4 m per second or at a muzzle energy exceeding 5.7 Joules, or

(ii) a shot, bullet or other projectile that is designed or adapted to attain a velocity exceeding 152.4 m per second or an energy exceeding 5.7 Joules.

Exception — antique firearms

(3.1) Notwithstanding subsection (3), an antique firearm is a firearm for the purposes of regulations made under paragraph 117(h) of the Firearms Act and subsection 86(2) of this Act.

ANTIQUE REGULATIONS

The firearms listed in the schedule are antique firearms for the purposes of paragraph (b) of the definition antique firearm in subsection 84(1) of the Criminal Code.

Black Powder Reproductions

1 A reproduction of a flintlock, wheel-lock or matchlock firearm, other than a handgun, manufactured after 1897.

2 A rifle manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging only rim-fire cartridges, other than 22 Calibre Short, 22 Calibre Long or 22 Calibre Long Rifle cartridges.

3 A rifle manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging centre-fire cartridges, whether with a smooth or rifled bore, having a bore diameter of 8.3 mm or greater, measured from land to land in the case of a rifled bore, with the exception of a repeating firearm fed by any type of cartridge magazine.

Shotguns

4 A shotgun manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging only rim-fire cartridges, other than 22 Calibre Short, 22 Calibre Long or 22 Calibre Long Rifle cartridges.

5 A shotgun manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging centre-fire cartridges, other than 10, 12, 16, 20, 28 or 410 gauge cartridges.

Handguns

6 A handgun manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging only rim-fire cartridges, other than 22 Calibre Short, 22 Calibre Long or 22 Calibre Long Rifle cartridges.

7 A handgun manufactured before 1898 that is capable of discharging centre-fire cartridges, other than a handgun designed or adapted to discharge 32 Short Colt, 32 Long Colt, 32 Smith and Wesson, 32 Smith and Wesson Long, 32-20 Winchester, 38 Smith and Wesson, 38 Short Colt, 38 Long Colt, 38-40 Winchester, 44-40 Winchester, or 45 Colt cartridges.

FIREARMS REGULATIONS

These regulations list a number of firearms that are prohibited or restricted, and also lists prohibited devices such as high capacity magazines, silencers, replica firearms, and prohibited ammunition. These regulations provide standards for magazines to ensure that they are permanently modified to contain only the maximum legal number of cartridges.

Definition of Semi-automatic

“semi-automatic”, in respect of a firearm, means a firearm that is equipped with a mechanism that, following the discharge of a cartridge, automatically operates to complete any part of the reloading cycle necessary to prepare for the discharge of the next cartridge.

“ASSAULT WEAPONS BAN 2020”

More information about the firearms ban can be found here.

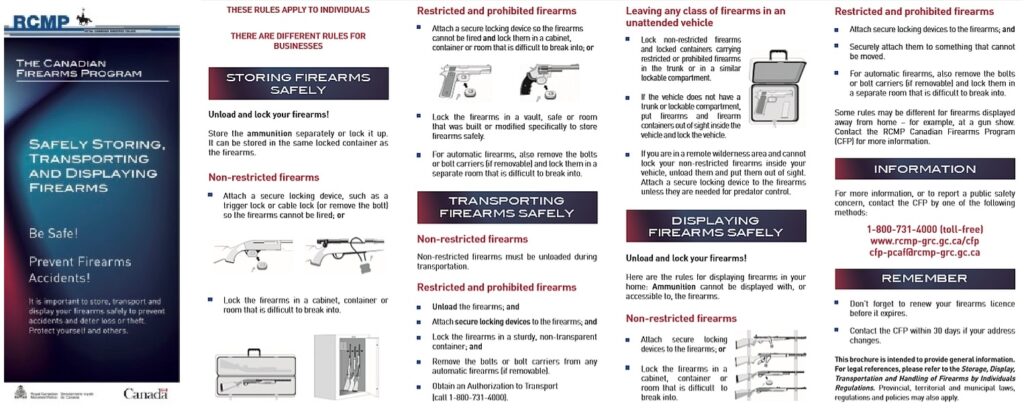

STORAGE REGULATIONS

Unloaded, in respect of a firearm, means that any propellant, projectile or cartridge that can be discharged from the firearm is not contained in the breech or firing chamber of the firearm nor in the cartridge magazine attached to or inserted into the firearm.

Secure locking device means a device

(a) that can only be opened or released by the use of an electronic, magnetic or mechanical key or by setting the device in accordance with an alphabetical or numerical combination; and

(b) that, when applied to a firearm, prevents the firearm from being discharged.

What is a “Safe” for the purposes of the Storage Regulations

COMPETITION HANDGUNS

LIST OF PRESCRIBED EXCLUDED HANDGUNS

1 Benelli MP 90 S 32 S&W Long

2 Domino OP 601 22 Short

3 Erma ESP 85A 32 S&W Long

4 FAS CF 603 32 S&W Long

5 FAS 601 22 Short

6 Hammerli-Walther 201 22 Short

7 Hammerli-Walther 202 22 Short

8 Hammerli 230 22 Short

9 Hammerli 230-1 22 Short

10 Hammerli 230-2 22 Short

11 Hammerli 232 22 Short

12 Hammerli 280 32 S&W Long

13 Hammerli P240 32 S&W Long

14 Hammerli SP-20 22 LR

15 Hammerli SP-20 32 S&W Long

16 High Standard Olympic 22 Short

17 Manurhin MR 32 Match 32 S&W Long

18 Pardini GP 22 Short

19 Pardini GP Schumann 22 Short

20 Pardini HP 32 S&W Long

21 Pardini MP 32 S&W Long

22 Sako 22-32 22 Short

23 Sako 22-32 22 LR

24 Sako 22-32 32 S&W Long

25 Sako Tri-Ace 22 Short

26 Sako Tri-Ace 22 LR

27 Sako Tri-Ace 32 S&W Long

28 Unique DES 69 22 LR

29 Unique VO 79 22 Short

30 Unique DES 32 U 32 S&W Long

31 Vostok TOZ 96 32 S&W Long

32 Walther GSP 22 LR

33 Walther GSP 22 Short

34 Walther GSP 32 S&W Long

35 Walther OSP 22 LR

36 Walther OSP 22 Short

37 Walther OSP 32 S&W Long

FIREARMS ACT

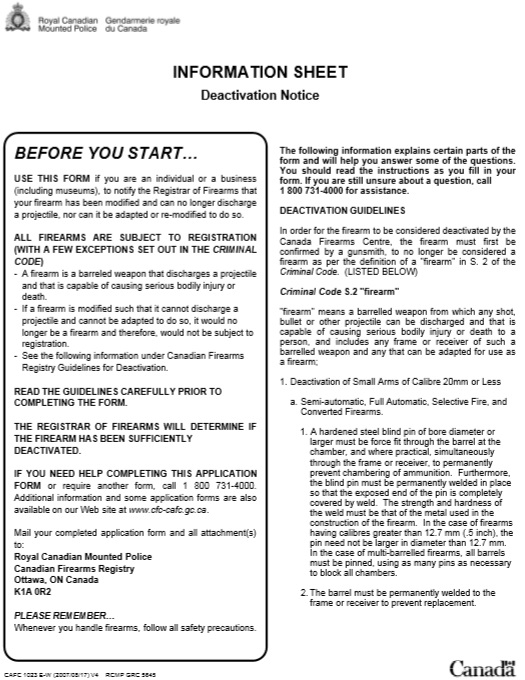

DEACTIVATION GUIDELINES

In order for the firearm to be considered deactivated by the RCMP Canadian Firearms Program (CFP), the firearm must first be confirmed by a gunsmith, to no longer be considered a firearm as per the definition of a “firearm” in S. 2 of the Criminal Code.

FIREARMS LICENCES

HISTORY OF FIREARMS IN CANADA

https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/history-firearms-canada

The 19th century

Before 1892, you weren’t allowed to carry a handgun if you didn’t have reasonable cause to fear assault against your life or property. Justices of the Peace could impose a six-month jail term on anyone carrying a handgun without cause.

In 1892, the first Criminal Code required you to have a basic permit to carry a pistol unless you had cause to fear assault or injury. This was known as a certificate of exemption.

Vendors could no longer sell a pistol to anyone under 16.

Vendors who sold pistols or air guns had to keep a record of:

- the purchaser’s name

- the date of the sale

- information that could identify the gun

The 20th century

1913

If the police caught you carrying a handgun outside the home or place of business without a permit, you could get a three-month sentence.

You could no longer transfer a firearm to any person under the age of 16. People under the age of 16 could also not buy a firearm.

The government created the first specific search, seizure and forfeiture powers for firearms and other weapons.

1919 to 1920

A Criminal Code amendment required you to get a permit to possess a firearm, no matter where you kept the firearm. You could get these permits from a magistrate, a chief of police or the RCMP.

British subjects didn’t need a permit for shotguns or rifles they already owned. They only needed one for newly acquired firearms.

Permits were valid for one year within the issuing province.

There was no central registry. Local authorities maintained records.

1921

A Criminal Code amendment repealed the requirement for everyone who had a firearm to have a permit. Instead, only non-Canadians needed a permit to have firearms. (British subjects still needed a permit to carry pistols or handguns).

1932 to 1933

Before 1932, to get a permit for a handgun, you only needed to be of “discretion and good character”. Starting in 1932, you also had to give reasons for wanting a handgun.

You could only get a permit for a handgun if you were:

- protecting life or property

- Intending to use a firearm at an approved shooting club

The government lowered the minimum age for having firearms from 16 to 12 years.

The government created the first mandatory minimum consecutive sentence. It was 2 years for the possession of a handgun or concealable firearm while committing an offence.

The government increased the punishment for carrying a handgun outside the home or place of business from 3 months to a maximum of 5 years.

1934

The government created the first real registration requirement for handguns. Before then, when a permit holder bought a handgun, the person who issued the permit was notified. The new provisions required records identifying:

- the owner

- the owner’s address

- the firearm

These records weren’t centralized.

The Commissioner of the RCMP or police departments designated as firearms registries issued registration certificates and kept records.

1938

Starting in 1939, you had to re-register your handguns every five years. Before this, certificates were valid indefinitely.

Guns didn’t need to have serial numbers, but it became an offence to alter or deface numbers.

The government extended the mandatory 2-year minimum sentence for using a firearm while committing an offence to include the use of any type of firearm in an offence, not just handguns and concealable firearms.

The government raised the minimum age to own a firearm from 12 to 14 years. If you were under 14, you could have access to firearms if you had a “minor’s permit”.

1939 to 1944

The government postponed re-registration because of World War II.

During the war years, you had to register rifles and shotguns. The government discontinued this after the war ended.

1947

The government expanded the parts of the Criminal Code dealing with “constructive murder” to include any case where a death resulted from the possession or use of any weapon, including any firearm, during the commission of an offence, even if the offender did not intend to kill.

1949

A 1949 Supreme Court decision (R. v. Quon) found that the 2-year mandatory minimum sentence did not apply to common crimes such as armed robbery. It was repealed.

1950

Changes to the Criminal Code meant that you no longer had to renew registration certificates. Certificates became valid indefinitely.

1951

The government centralized the registry system for handguns under the Commissioner of the RCMP.

You now had to register automatic firearms, and these firearms now had to have serial numbers.

1968 to 1969

The government created the categories of “firearm”, “restricted weapon” and “prohibited weapon”. This ended confusion over specific types of weapons. It also allowed the creation of legislative controls for each of the new categories. The new definitions allowed Order-in-Council to designate weapons as prohibited or restricted.

The government increased the minimum age to get a minor’s permit to 16.

For the first time, police could search for firearms and seize them if:

- they had a warrant from a judge

- they had reasonable grounds to believe that possession endangered the safety of the owner or any other person, even though no offence had been committed

The current registration system, requiring a separate registration certificate for each restricted weapon, took effect in 1969.

1976

The government introduced Bill C-83. Its proposals included:

- New offences and stricter penalties for the criminal misuse of firearms

- The prohibition of fully automatic firearms

- A licensing system requiring anyone aged 18 or older to get a licence to acquire or possess firearms or ammunition

- People under 18 were eligible only for minors’ permits

The licensing provisions were based on the idea that people should have to show fitness and responsibility before they could use firearms. Bill C-83 would have required licence applicants to include statements from two people willing to guarantee their fitness.

The Bill died on the Order Paper in July.

1977

Bill C-51 passed in the House of Commons. It then received Senate approval and Royal Assent on August 5. The two biggest changes included requirements for:

- Firearms Acquisition Certificates

- Firearms and Ammunition Business Permits

The bill also introduced Chief Firearms Officer positions in the provinces.

Other changes included:

- Provisions dealing with new offences

- Search and seizure powers

- Increased penalties

- New definitions for prohibited and restricted weapons

Fully automatic weapons became prohibited firearms unless they were registered as restricted weapons before January 1, 1978. You could no longer carry a restricted weapon to protect property.

The government reintroduced mandatory minimum sentences. This time, they were in the form of a 1-to 14-year consecutive sentence for the actual use (not mere possession) of a firearm to commit an indictable offence.

1978

All the provisions contained in Bill C-51 came into force, except for the requirements for Firearms Acquisition Certificates and for Firearms and Ammunition Business Permits.

1979

The requirements for Firearms Acquisition Certificates and Firearms and Ammunition Business Permits came into force. Both involved the screening of applicants and record-keeping systems. Provinces could require Firearms Acquisition Certificate applicants to take a firearm safety course.

1990

The government introduced Bill C-80 but it died on the Order Paper. Many of the proposals contained in Bill C-80 were later included in Bill C-17.

Among the major changes proposed by Bill C-80 were:

- The prohibition of automatic firearms converted to semi-automatics to avoid the 1978 prohibition

- The creation of new controls for other types of military or para-military firearms

- Better screening of Firearms Acquisition Certificate applicants

1991 to 1994

The government introduced Bill C-17. The bill:

- passed in the House of Commons on November 7

- received Senate approval and Royal Assent on December 5, 1991

- came into force between 1992 and 1994

Changes to the Firearms Acquisition Certificate system included:

- Requiring applicants to provide a photograph and two references

- Imposing a mandatory 28-day waiting period for an Firearms Acquisition Certificate

- A mandatory requirement for safety training

- Expanding the application form to provide more background information

- More detailed screening check of Firearms Acquisition Certificate applicants

Some other major changes included:

- Increased penalties for firearm-related crimes

- New Criminal Code offences

- New definitions for prohibited and restricted weapons

- New regulations for firearms dealers

- Clearly defined regulations for the safe storage, handling and transportation of firearms

- A requirement that firearm regulations be drafted for review by parliamentary committee before being made by Governor-in-Council

A major focus of the new legislation was the need for controls on military, paramilitary and high-firepower guns. New controls in this area included:

- The prohibition of large-capacity cartridge magazines for automatic and semi-automatic firearms

- The prohibition of automatic firearms that were converted to avoid the 1978 prohibition (existing owners were exempted)

- A series of Orders-in-Council prohibiting or restricting most paramilitary rifles and some types of non-sporting ammunition

Firearms Acquisition Certificate applicants had show knowledge of the safe handling of firearms starting in 1994. To show knowledge, you either:

- had to pass the test for a firearms safety course approved by a provincial Attorney General

- needed a firearms officer to certify that you could handle firearms safely

Safety courses had to now cover firearms laws as well as safety issues.

After the 1993 federal election, the new government wanted to proceed with further controls. These included some form of licensing and registration system that would apply to all firearms and their owners. Provincial and federal officials met several times to define issues related to universal licensing and registration proposals.

Between August 1994 and February 1995, the government defined the options for policy and drafted new legislation.

1995

The government introduced Bill C-68 on February 14. Senate approval and Royal Assent were granted on December 5, 1995. Major changes included:

- Criminal Code amendments providing harsher penalties for certain serious crimes using firearms (e.g., kidnapping, murder)

- The creation of the Firearms Act, to take the administrative and regulatory aspects of the licensing and registration system out of the Criminal Code

- A new licensing system to replace the Firearms Acquisition Certificate system

- You had to have a licence to possess and acquire firearms, and to buy ammunition

- Registration of all firearms, including shotguns and rifles

The Firearms Registrar issued registration certificates. The registrar was responsible for registering firearms owned by individuals and businesses.

The Firearms Act allowed for the appointment of ten Chief Firearms Officers, one for each province. Some provinces also included a territory. Provincial or federal governments could appoint Chief Firearms Officers. Chief Firearms Officers were responsible for issuing, renewing, and revoking firearms licences.

1996

The provisions requiring mandatory minimum sentences for serious firearms crimes came into effect in January. The Canada Firearms Centre developed the regulations, systems and infrastructure needed to implement the Firearms Act. To ensure that the regulations reflected the needs of Canadians, officials consulted with:

- the provinces and territories

- groups and individuals with an interest in firearms

The Minister of Justice tabled proposed regulations on November 27. These dealt with:

- All fees payable under the Firearms Act

- Licensing requirements for firearms owners

- Safe storage, display and transportation requirements for individuals and businesses

- Authorizations to transport restricted or prohibited firearms

- Authorizations to carry restricted firearms and prohibited handguns for limited purposes

- Authorizations for businesses to import or export firearms

- Conditions for transferring firearms from one owner to another

- Record-keeping requirements for businesses

- Adaptations for Indigenous Peoples

1997

In January and February, a government committee held public hearings on the proposed regulations. Following the hearings, the committee made 39 recommendations to improve the regulations. They clarified the provisions and recognized the needs of firearms users. The committee also recommended that the government develop communications programs to inform Canadians about the new law.

In April, the Minister of Justice tabled the government’s response. The government accepted all but one of the committee’s 39 recommendations. It rejected a recommendation for an additional step in the licence approval process.

In October, the Minister of Justice tabled some amendments to the 1996 regulations as well as regulations dealing with:

- firearms registration certificates

- exportation and importation of firearms

- the operation of shooting clubs and shooting ranges

- gun shows

- special authority to possess

- public agents

1998

The Firearms Act, Bill C-68, came into force on December 1. The government passed the Firearms Act Regulations in March.

The following provinces and territories opted out of administering the act themselves:

- Alberta

- Saskatchewan

- Manitoba

- The Northwest Territories

The RCMP oversaw the Chief Firearms Officers for these jurisdictions.

The 21st century

2001

Starting January 1, you needed a licence to possess and acquire firearms.

The RCMP created the National Weapons Enforcement Support Team to support law enforcement in stopping the illegal movement of firearms. This team also helped police agencies with:

- Investigative support

- Training and lectures

- Analysis

- Firearms tracing

- Expert witnesses

- Links to a network of national and international firearms investigative groups

2002

The following provinces and territories opted out of administering the act themselves:

- British Columbia

- Yukon Territory

- Newfoundland and Labrador

The RCMP oversaw the Chief Firearms Officers for these jurisdictions.

2003

Starting January 1, you needed a valid licence and registration certificate for all firearms in your possession. This included non-restricted rifles and shotguns.

Firearms businesses also needed a valid business licence and registration certificate for all their firearms.

The Canada Firearms Centre became an independent agency within the Solicitor General Portfolio.

On May 13, Bill C-10A, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Firearms) and the Firearms Act received Royal Assent. The government consolidated the authority of all operations under a Commissioner of Firearms. The commissioner reported directly to the Solicitor General.

In June, the government tabled proposed amendments to the regulations supporting the Firearms Act. Consultations with key stakeholders about the proposed regulations took place in the fall of 2003.

2005

Some Bill C-10A regulations came into effect, specifically the ones that would:

- improve service delivery

- streamline processes

- improve transparency and accountability

2006

Responsibility for the administration of the Firearms Act and the operation of the Canada Firearms Centre transferred to the RCMP in May 2006. The Commissioner of the RCMP assumed the role of the Commissioner of Firearms.

In June, the government tabled Bill C-21, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act. It was intended to repeal the requirement to register non-restricted firearms. It dies on the order paper.

2007

The government reintroduced Bill C-21 as Bill C-24.

2008

The RCMP amalgamated all firearms-related groups into the Canadian Firearms Program.

Bill C-24 died on the order paper in September.

The rest of the Public Agents Firearms Regulations came into force on October 31. Police and other government agencies with firearms needed to report all firearms in their temporary or permanent possession.

2011

On October 25, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness introduced Bill C-19, An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act (Ending the Long-gun Registry Act).

2012

On April 5, Bill C-19, the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act, came into force. The bill amended the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act to:

- remove the requirement to register non-restricted firearms

- order the destruction of existing registration records

- allow the transferor of a non-restricted firearm to confirm the validity of a transferee’s firearms acquisition licence before finalizing the transfer

On April 4, the Government of Quebec filed a court challenge to Bill C-19. As a result, the government kept non-restricted firearms registration records for Quebec. Quebec residents continued to register non-restricted firearms.

In October, the government destroyed all non-restricted firearms registration records, except for Quebec’s.

2015

On March 27, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed Quebec’s appeal challenging the parts of the Ending the Long Gun Registry Act that required the destruction of the non-restricted registration records. The court also refused to order the transfer of these records to Quebec. As a result, the Canadian Firearms Program stopped accepting and processing registration/transfer applications for non-restricted firearms from Quebec. The government destroyed all official records related to the non-restricted firearms in Quebec.

On June 18, Bill C-42, the Common Sense Firearms Licensing Act, received Royal Assent. These provisions came into force:

- First-time licence applicants had to take part in classroom firearms safety courses

- The discretionary authority of Chief Firearms Officers became subject to the regulations

- Stronger Criminal Code provisions relating to prohibiting the possession of firearms when a person is convicted of an offence involving domestic violence

- The Governor in Council had the authority to prescribe firearms to be non-restricted or restricted

On September 2, two additional provisions of the Common Sense Firearms Licensing Act came into force:

- the elimination of the Possession Only Licence and conversion of all existing Possession Only Licences to Possession and Acquisition Licences

- the Authorization to Transport became a condition of a licence for certain routine and lawful transportation activities

The provision that created a six-month grace period at the end of a five-year licence came into force in 2017. The provision for permitting the sharing of firearms import information when businesses import restricted and prohibited firearms into Canada is not yet in force.

2018

The government tabled Bill C-71, An Act to amend certain Acts and Regulations in relation to firearms, in March to:

- strengthen the federal firearms regulatory regime

- provide law enforcement with better tools to help solve firearms-related crimes

2019

On June 21, the government announced that Bill C-71 received Royal Assent.